Diego Rivera’s Maize: Huasteca Culture

Some of Rivera’s most famous mural work revealed a complex Representation of Mesoamerican Food Culture and Twentieth Century Mexican Identity

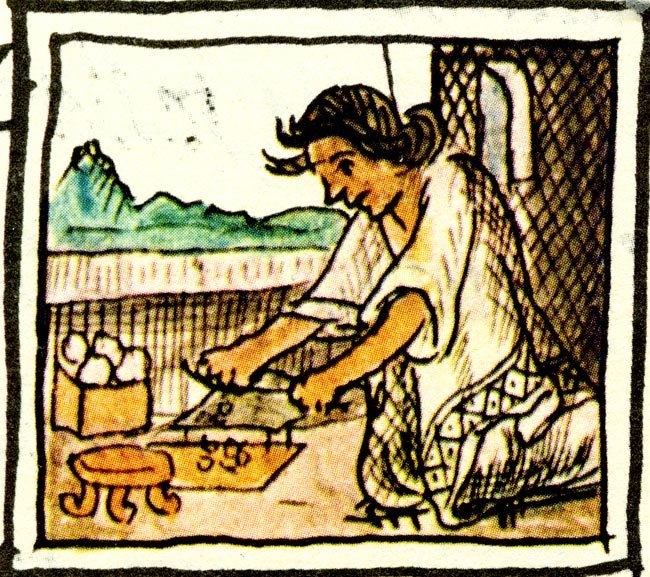

Preparing maize, from The Florentine Codex, Book 10.

Food is understood as inextricable from culture and collective ideas about the foundations of national identity. Cultural anthropologist Nir Avieli asserts that “cuisine is essential to nation-building, as it allows a people to define themselves by what they eat in contrast to what others eat…”[1] From farming to its preparation and ritual consumption, food is an integral part of the histories of nations: as quotidian in the lives of every person, in creating structures of civilizations, and the ways in which it is acted upon by power. In the pre-contact civilizations of Mexico, food carried specific meanings, and feasts and rituals were constructed to celebrate the harvest and honour gods. We can see depictions of food and drink on Mayan pottery vessels, of food culture in the Florentine Codex, and as an important theme in the of post-revolutionary ideals as seen in the work of Diego Rivera (1886-1957).

Food offerings to Chicomecóatl (‘Seven Snake’), goddess of maize, during the ‘Great Vigil’ festival, Florentine Codex, Book 2

By engaging with Rivera’s 1950 work, Maize: Huesteca Cultura, we can construct an argument for the role of both food and art in nation building. By performing a close reading of the painting’s content and examining the work’s provenance in the context of the political and social agendas at play in post-revolutionary Mexico, this paper will explore the intersection between food and national identity, and how this meaning was expressed in this work by Rivera. I will also discuss how and why, in the larger context of the emergence of Mexico as an independent republic and subsequent nation-building activities, Rivera chose to depict the importance of agriculture, food, and specifically corn in his representations of Mesoamerican culture.

Post-revolutionary Mexico was a time for the country to establish and legitimize its identity as an independent republic, and many of the policies put in place to extend the hand of government into rural areas hinged on the belief that indigenous peoples lacked education and required modernization.[2] In the Cárdenas era of the late 1930s and 40s, believing that the history of Mexico was grounded in Indigenous heritage, Cárdenas introduced policies aimed at further supporting and disseminating Indigenous art, music, language, and culture, promoting them to the greater population of Mexico.[3] By extension, artists and intellectuals of the time, including Rivera, were commissioned to translate these ideals into public art.[4] Returning to Mexico in 1922 after an apprenticeship in Europe, Diego Rivera, himself of Amerindian descent, stated upon his return to his homeland he was “reborn”.[5] He visited archeological sites and began to explore Indigenous history in his works, many of which were commissioned under the cultural reform activities of education minister Jose Vasconcelos. Beginning in the 1920s, Rivera embarked on a series of government-sponsored murals. The national campaign to promote Indian culture continued into 1940s and 50s, when Rivera painted Maize: Huesteca Cultura in the hallway leading to his epic History of Mexico mural in the Palacio Nacionale in Mexico City. By depicting Mesoamerican people performing the tasks of growing, harvesting, and preparing food, Rivera demonstrated the importance of Mexican food heritage in broader Mexican culture, it’s significance in the pursuit of a unified post-Revolutionary nation-state, and in forging Mexico’s identity. Civilizations, and nations are born and survive on the foods they cultivate and the culinary traditions that arise from them. It makes sense to ask questions about the role that food plays in Rivera’s Huasteca Cultura.

As the main staple food of Mesoamerica, maize specifically was not only a source of nourishment but was endowed with religious and cultural meaning across era and the civilizations that dominated them.[6] In the Aztec belief system, corn was seen as the manifestation of the maize god Centeotl, and the very source of human life. For the Maya, the creation story of humans was based on the belief that they were created from maize by the gods; the Popul Vuh describes the highest form of first peoples fashioned from corn dough. The Mexica believed that humans were made of the dough of white corn, and in Centeōtl and Chicomecōātl, god and goddess of maize.[7] Corn was seen as the very origin of all humanity.[8] In 1519, Cortes encountered that vast food markets at Tenochtitlán, and even today, in his letters to King Charles I of Spain, we can appreciate his palpable astonishment as he relays the sheer variety of foods he found there: “...all sorts of vegetables…many kinds of fruits…honey of a plant called maguey, which is better than most; from these plants they make sugar and wine…maize, both in grain and made into bread, which is very superior in its quality…pies of birds and fish…eggs of hens, and geese, and other birds in great quantity, and cakes made of eggs.”[9] These foods and others were offered as tribute by conquered people to their conquerors. The rise of Mesoamerican civilisations could not have been realized without the cultivation of maize, as well as nixtamalization, the process by which dried maize is soaked in lime to soften it and make its nutrients more accessible, and the grinding of corn into a form that could be used to make foodstuffs such as tortillas.[10] This was crucial to the rise of the Aztec specifically: this skill contributed to the civilisation’s specialised economy and ground and dried corn became a portable food that nourished other specialised workers.[11]

In choosing to depict Mesoamerican food — specifically corn — as a symbol of nationalism, Rivera was carrying on a history of the foods of Mexico being used to exemplify political ideologies. During the Porfiriato era of late 19th and early 20th centuries, the elites of Mexico distanced themselves from their Indigenous heritage by abandoning traditional foods in favour of nouvelle French cuisine[12], while nineteenth century pre-revolution Mexican cookbooks cleaved indigenous culinary heritage from “respectable” cooking by excluding dishes made of maize from their pages.[13]

The creation of Huasteca Cultura was preceded by the institution of specific cultural and social reforms that were manifested in artistic works commissioned by José Vasconcelos, secretary of education under President Obregón. Vasconcelos had known Rivera from their mutual membership in the radical student-led group Youth Atheneum[14] and called him back from a painting apprenticeship in Europe to begin what would be the first wave of mural projects depicting the past and future Mexico, encouraging him to examine previously ignored areas of Mexican society: indigenous and peasant communities.[15] The second of two commissions to paint a series of murals in the Palacio Nacionale in Mexico City began in 1941. In the post-war and early cold war era, nations across the globe were subjected to massive cultural and social changes and shifting borders. While Mexico industrialized under President Manuel Avila-Camacho, government and intellectual elites were inspired to define and foster an updated national identity.[16] Avila-Camacho’s nationalist ideologies included the mestizaje policy: the idea that a unified Mexican cultural identity would be realized by mixing races, a goal that would effectively subsume Indigenous groups.[17] In his art, Rivera continued to look to pre-Columbian civilizations as the roots of Mexican identity,[18] however the principles of mestizaje dictated that indigeneity was important only as a link to Mexico’s past: a relic to be appreciated but not part of the vision for modern Mexico. Rivera accepted the commission, though it isn’t clear if he agreed with mestizaje as a motivation and may have had his own reasons for doing so. The Huastec people are themselves not relics: populations still live in and are landowners in San Luis Potosí, Tamaluipas, and the north of Veracruz.[19] While Rivera himself claimed to be of mixed blood, with ancestors of Indigenous, Spanish, Italian, Jewish, and Portuguese descent,[20] he made no secret of his contempt for Spaniards.[21] A lifelong hypochondriac, believed he would die early of cancer, as his parents had, and dreamed that before he did, we would paint pre-Colombian Tenochtitlan “as it had been, before the barbaric Spanish invaders destroyed its beauty.”[22] He desired to portray indigenous history as dignified, and believed that the contributions of Mesoamericans to civilization far outweighed what industrialisation had achieved.[23] Whatever his actual motives for accepting the commission, beyond money and prestige, Rivera likely saw the opportunity as a lucrative vehicle for his Marxist ideals.[24] To this end, he painted Huasteca Cultura as one of eleven panels applied to the palace corridors surrounding the patio. In this series of murals, we can see two distinct themes: a culturally vital and technologically advanced pre-Columbian Mexico, and the damage done to Indigenous cultures by Spaniards. The eleven panels of the corridor murals depicted the indigenous civilisations and their contributions to the culture of Mexico, including agriculture, herbal medicine, botany, mathematics, astronomy, engineering, urban planning, and architecture. Illustrations of food included the agricultural products exported to the New World, including chocolate, tomatoes, peanuts, avocado, and corn.[25]

By the time Rivera painted Huesteca Cultura in 1950, the industrialization of food that began in the early part of the century had already made the production of traditional food items like tortillas a standardized and mechanized process. The early 20th century saw the introduction of the molino de nixtamal, a machine for grinding corn that shortened the hours-long tortilla-making process that was primarily the task of women.[26] Mexican cuisine had also straddled the borders constructed by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and the lines of American and Mexican food had blurred into the beginnings of Tex-Mex cuisine.[27] This was emblematic of the real fear that Mexican elites felt at the possible loss of cultural autonomy to the United States, and led to the policies that sought to ground Mexican nationalism in its indigenous past.[28] Ironically, it was not the elites, but rural Mexicans who continued to prepare maize and other pre-contact foods using traditional methods[29], these so-called “illiterates” being a target audience for the historical education policies of the mural projects.[30]

Huesteca Cultura is the eighth panel and depicts a paradise of idealized Indigenous life.[31] It is rendered in a combination of highly pigmented fresco and at the bottom, a panel of grisaille (not shown), a monochrome grey application that mimics architectural relief.[32] The saturation of the colours came from Rivera’s use of natural pigments, ground by hand by his assistants and thinned with water to make a paste, which he applied to the wall.[33] Rivera shows the collective, almost joyful, participation of the community in planting, harvesting, grinding, and cooking corn. In the foreground, men tend the corn crop while the women, some young with babies, and one old, use a metate to grind the corn to be made into tortillas or atole, a corn-based hot drink. They work under the watchful eyes of Chicomecōātl, the fertility goddess of agriculture responsible for the growing of maize, clothed in dazzling colours and carrying ears of corn.

Maize: Huasteca Cultura. 1950. Diego Rivera. Palacio Nacionale, Mexico City.

She is a magnificent and imposing presence, guiding her people through a process that would nourish both physically and spiritually. Despite working in the hot sun to plant and the hours of physical labour involved in grinding corn by hand, the serene faces of the Huastec people do not belie any fatigue, and they seem at peace with their work. Their bodies are idealized: the men’s skin burnished to a deep copper by toiling in the sun, and the women, both naked and clothed, are healthy and curvaceous, their naked breasts and strapped on baby suggesting ideal womanliness and fecundity. The older woman is as strong and capable in her work as the younger, perhaps symbolic of the past being relevant to the future, represented by the image of the baby, and the present, shown in the women whose varying ages lie between. The foreground perspective has been flattened to fit in the depictions of the many stages of growing, grinding, and cooking with corn. The perspective is then dramatically elongated to show a long view of the technical achievements of irrigation and causeways, while the perfectly straight lines of the verdant fields demonstrate agricultural prowess. Just beyond lies the glittering city, overlooked by majestic mountains. An important distinction to note is that in this specific fresco of Rivera’s, the connection between corn—and the food products made from it—and national identity did not privilege the food itself, but the success of the technologies developed by the Indigenous to produce it. The painting deliberately depicts the chinampas: the floating beds that allowed for easy irrigation of the crops; the basic and effective digging sticks used to delineate rows for seeding, remove weeds and aerate the soils around plants; the healthy corn is perfectly ripe and towers over the men; the lava-stone metate for grinding the corn, a basalt molcajete and tejolote (mortar and pestle), the cazuela pot for soaking the corn in lime, and other pieces of pottery for storage.[34] That the painting is juxtaposed against the Palacio murals depicting the golden age of industry in Mexico, under the watchful eyes of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin, and amid workers and soldiers, is not accidental. Rivera said that “each personage in the mural was dialectically connected with his neighbours, in accordance with his role in history. Nothing was solitary; nothing was irrelevant…”[35] In his idealization the pre-conquest world, he deftly compared it to the industrialized era in which it the work was created, reinforcing the idea that anything achieved the modern world had been already perfected by the Mesoamerican one. This approach foregrounded the importance of Indigenous peoples in the process of achieving a modern Mexico.

Rivera’s role has been characterized as essentially the artist in residence for the ruling government, and his motives for creating his murals have been debated and contested.[36] Huasteca Cultura is but one fraction of this body of work, and a better analysis could come from a more wholistic approach to the work’s placement within it, however we can say that by using food as a proxy for the state’s messages of nationalism, Rivera was tapping into the both the nostalgia of ancient foodways and demonstrating the efficacy of food culture —including the technologies developed by Mesoamericans to produce it — in representing the longevity and uniqueness of Mexico into the modern age.

Notes

[1] Nir Avieli, Food and Power: A Culinary Ethnography of Israel, California Studies in Food and Culture (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2017), 11.

[2] Enrique Ochoa, “Introduction: Food and Society on Post-Revolutionary Mexico,” in Feeding Mexico: The Political Uses of Food since 1910 (The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2000), 4.

[3] Anne Doremus, “Indigenism, Mestizaje, and National Identity in Mexico during the 1940s and the 1950s,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 17, no. 2 (August 1, 2001): 377, https://doi.org/10.1525/msem.2001.17.2.375.

[4] Doremus, 378.

[5] Diego Rivera and with Gladys March, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography (Courier Corporation, 2012), 72.

[6] Zilkia. Janer, Latino Food Culture, Food Cultures in America (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2008), 2.

[7] Sheila Layton Scoville, “Decolonizing Taste: A Mesoamerican Staple in Colonial and Contemporary Art” (Houston, Texas, University of Houston, 2020), 4.

[8] Janer, Latino Food Culture, 2.

[9] Nora E. Jaffary, Edward W. Osowski, and Susie S. Porter, Mexican History: A Primary Source Reader (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2010), 41–42.

[10] Scoville, “Decolonizing Taste,” 3.

[11] Paula Turkon, “Food Preparation and Status in Mesoamerica,” in Archaeology of Food and Identity (Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, 2007), 155.

[12] Jeffrey M. Pilcher, “Tamales or Timbales: Cuisine and the Formation of Mexican National Identity, 1821-1911,” The Americas 53, no. 2 (1996): 196, https://doi.org/10.2307/1007616.

[13] Jeffrey M. Pilcher, Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), xiv.

[14] Margarita Vera Cuspinera, “José Vasconcelos,” in Encyclopedia of Mexico (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997), 1519.

[15] Renato González Mello, “Manuel Gamio, Diego Rivera, and the Politics of Mexican Anthropology,” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 45 (March 2004): 161, https://doi.org/10.1086/RESv45n1ms20167626.

[16] Manuel Aguilar-Moreno and Erika Cabrera, Diego Rivera: A Biography (ABC-CLIO, 2011), 81.

[17] Doremus, “Indigenism, Mestizaje, and National Identity in Mexico during the 1940s and the 1950s,” 376.

[18] Aguilar-Moreno and Cabrera, Diego Rivera, 81.

[19] Aguilar-Moreno and Cabrera, 85.

[20] Rivera and March, My Art, My Life, 1.

[21] Aguilar-Moreno and Cabrera, Diego Rivera, 86.

[22] Betram D. Wolfe, The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera (Cooper Square Press, 2000), 367.

[23] Aguilar-Moreno and Cabrera, Diego Rivera, 86.

[24] Leonard Folgarait, “Revolution as Ritual: Diego Rivera’s National Palace Mural,” Oxford Art Journal 14, no. 1 (1991): 31, http://www.jstor.org.subzero.lib.uoguelph.ca/stable/1360275.

[25] Aguilar-Moreno and Cabrera, Diego Rivera, 82.

[26] John C. Super and Luis Alberto Vargas, “Mexico and Highland Central America,” in The Cambridge World History of Food, ed. Kenneth F. Kiple and Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas, 1st ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2000), 1252, https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521402156.016.

[27] Pilcher, Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, xiv.

[28] Pilcher, xiv.

[29] Pilcher, “Tamales or Timbales,” 195–96.

[30] “Mexican Muralism: Los Tres Grandes David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco (Article) | Khan Academy,” accessed December 11, 2022, https://www.khanacademy.org/_render.

[31] Aguilar-Moreno and Cabrera, Diego Rivera, 82.

[32] Aguilar-Moreno and Cabrera, 86.

[33] Wolfe, The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera, 179.

[34] Jeffrey M. Pilcher, “Corn People,” in Que Vivan Los Tamales!: Food and the Making of Mexican Identity (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), 11, http://inside.sfuhs.org/dept/history/Mexicoreader/Chapter1/CornPeople.pdf.

[35] Rivera and March, My Art, My Life, 101.

[36] Jeffrey Belnap, “Diego Rivera’s Greater America Pan-American Patronage, Indigenism, and H.P.,” Cultural Critique, no. 63 (2006): 61–62, http://www.jstor.org.subzero.lib.uoguelph.ca/stable/4489247.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Bernardino, Arthur J. O. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Santa Fe, N.M: School of American Research, 1950.

Rivera, Diego. “Huesteca Cultura.” Fresco. 1950. Palacio Nacionale, Mexico City.

Secondary Sources

Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel, and Erika Cabrera. Diego Rivera: A Biography. ABC-CLIO, 2011.

Anderso, Lara, Rebecca Ingram. “Introduction.” Transhispanic Food Cultural Studies: Defining the Subfield, Bulletin of Spanish Studies, 97:4, (2020): 471-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753820.2020.1702273

Belnap, Jeffrey. “Diego Rivera’s Greater America Pan-American Patronage, Indigenism, and H.P.” Cultural Critique, no. 63 (2006): 61–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4489247.

Doremus, Anne. “Indigenism, Mestizaje, and National Identity in Mexico during the 1940s and the 1950s.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 17, no. 2 (August 1, 2001): 375–402. https://doi.org/10.1525/msem.2001.17.2.375.

Folgarait, Leonard. “Revolution as Ritual: Diego Rivera’s National Palace Mural.” Oxford Art Journal 14, no. 1 (1991): 18–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360275.

Jaffary, Nora E., Edward W. Osowski, and Susie S. Porter. Mexican History : A Primary Source Reader. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2010.

Janer, Zilkia. Latino Food Culture. Food Cultures in America. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2008.

Mello, Renato González. “Manuel Gamio, Diego Rivera, and the Politics of Mexican Anthropology.” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 45 (March 2004): 161–85. https://doi.org/10.1086/RESv45n1ms20167626.

“Mexican Muralism: Los Tres Grandes David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco (Article) | Khan Academy.” Accessed December 11, 2022. https://www.khanacademy.org/_render.

Nir Avieli. Food and Power : A Culinary Ethnography of Israel. California Studies in Food and Culture. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2017.

Ochoa, Enrique. “Introduction: Food and Society on Post Revolutionary Mexico.” In Feeding Mexico: The Political Uses of Food since 1910. The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2000.

Paula Turkon. “Food Preparation and Status in Mesoamerica.” In Archaeology of Food and Identity, 152–73. Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, 2007.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. “Corn People.” In Que Vivan Los Tamales!: Food and the Making of Mexican Identity, 7–24. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

———. Planet Taco : A Global History of Mexican Food. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

———. “Tamales or Timbales: Cuisine and the Formation of Mexican National Identity, 1821-1911.” The Americas 53, no. 2 (1996): 193–216. https://doi.org/10.2307/1007616.

Rivera, Diego, and with Gladys March. My Art, My Life: An Autobiography. Courier Corporation, 2012.

Scoville, Sheila Layton. “Decolonizing Taste: A Mesoamerican Staple in Colonial and Contemporary Art.” University of Houston, 2020. https://www.proquest.com/openview/04c6c39427faf1d25945ee9aa6928a16/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=44156.

Super, John C., and Luis Alberto Vargas. “Mexico and Highland Central America.” In The Cambridge World History of Food, edited by Kenneth F. Kiple and Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas, 1st ed., 1248–54. Cambridge University Press, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521402156.016.

Vera Cuspinera, Margarita. “José Vasconcelos.” In Encyclopedia of Mexico. ChicagoFitzroy Dearborn, 1997.

Wolfe, Betram D. The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera. Cooper Square Press, 2000.